Lvxferre [he/him]

The catarrhine who invented a perpetual motion machine, by dreaming at night and devouring its own dreams through the day.

- 9 Posts

- 58 Comments

0·10 hours ago

0·10 hours agoAnyone willing to guess what’s the language in Linear A?

Personally I wouldn’t be surprised if it was:

- related to Etruscan and Lemnian

- Semitic

- non-Greek Indo-European (Anatolian?)

- some paleo-Balkan language unaffiliated with any of those.

I feel like both should be exactly in the middle, between FA and FO.

0·2 days ago

0·2 days agoThey can if they want, that’s 100% fine.

The goal here isn’t to concentrate the activity, but to encourage people to ask away, even if they feel like it is not worth creating a whole new thread for that.

0·2 days ago

0·2 days agoI learned about it in a rather off-topic way; syntax professor talking about Portuguese phrase structure, someone asks a question referring to a local variety, she answers to not assume the same structure for dialectal phenomena. Her example was the Jespersen’s cycle, something like:

- Não quero (standard negation, lit. “not want”) →

- Não quero, não (emphatic negation, lit. “not want, not”) →

- Quero não (dialectal, mostly Baiano and Mineiro; lit. “want not”)

She also mentioned other negative concord words (nenhum[a]/none, nada/nothing, etc.) might be undergoing the same process for the relevant dialects.

0·2 days ago

0·2 days agoOne thing I would add is that this video made it seem as though English is relatively unique in being stress-timed.

Indeed, it isn’t - it’s a really common feature across the world.

which, combined with English, suggests perhaps this is an ancestral feature of the Germanic family?

IMO it’s possible, but unlikely. Two reasons:

- PGerm had a 3-way vowel length contrast, so morae were likely a big deal in the language. Odds are that the language was either mora-timed (like Latin) or a middle ground between mora-timed and stress-timed.

- Isochrony changes really fast, diachronically speaking. Portuguese is a good example of that - all dialectal variation is ~600yo, and yet the language shows dialects all across the syllable-timed vs. stress-timed continuum.

0·3 days ago

0·3 days agoGeoff Lindsey has some damn great videos on English phonetics and phonology, I heavily recommend them; for example, this one, about the transcription of Standard Southern British vowels; to keep it short

- the diphthongs should be treated as vowel+consonant sequences, not as one vowel transitioning into another.

- /i: u:/ behave more like diphthongs than long vowels, and should be transcribed as such.

On the video shared by the OP, I think Lindsey made a great job highlighting that prosody is also a feature that a language may or may not use to convey information. English is mostly stress-timed (unless you’re Welsh, and specially if you also speak Welsh), so it uses prosodic stress a lot; in the meantime, Spanish (he compared EN and ES in his James Bond example) is mostly syllable-timed, so it barely uses this sort of reduction - if anything, quicker speech tends to attack consonants (cue to Chilean [äo] for /aðo/ -ado) way more often.

He also mentions L2 speakers; it’s worth noting prosody is a fucking pain to assimilate, so it’s no wonder that non-native speakers rarely use it. (Also, anecdotally speaking, I’ve noticed people highly proficient in a non-native language tend to let that language affect their native one’s prosody.)

0·3 days ago

0·3 days ago

I made this map a year or so ago, by superimposing two maps from Wikipedia. (If anyone wants I can dig the source maps.) Lancashire is that red “bubble” up north. Rhoticity is dying in the UK, and specially in England.

And while the feature alone is not a big deal, since it’s preserved elsewhere, it’s a sign that local varieties are dying - and those are pretty unique. They’re likely being replaced with Southern Standard British, by a death of a thousand cuts.

This also shows that claims that “American English” is killing the local dialects are likely false, otherwise you’d see an increase of rhoticity there. The local dialects are dying but due to country-internal pressures, such as identity; not due to simple media exposure. (This is, sadly, a rather typical pattern)

0·5 days ago

0·5 days agoConlang, right?

It’s completely fine to do some ad hoc IPA extensions when describing your conlang, just make sure to clarify them in the conlang files - both for others and for your future self. Or even ditch IPA and use a different notation system, made at home - specially when your conspeakers don’t have the same phonatory organs as humans would.

0·6 days ago

0·6 days agoNo because IPA only has symbols for segments and articulations that are attested in at least one language, and odds are that no language out there uses tongue rolled consonants:

- a lot of people can’t articulate it, so the articulation is rather unstable if you think about the linguistic community as a whole

- it takes considerable articulatory effort, and as you said it sounds a lot like other easier-to-pronounce sounds

For symbols for “odd” articulations like this you have a better chance checking extIPA (extended IPA). Originally it was intended for disordered speech, but often you see the symbols leaking even for descriptions of ordered speech. I couldn’t find one for tongue rolling though.

0·6 days ago

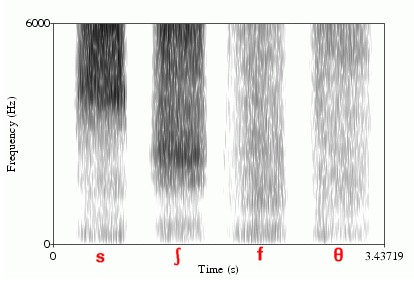

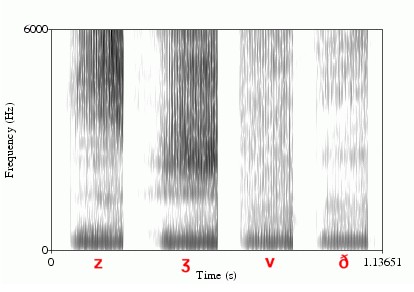

0·6 days agoSibilants are louder, specially in higher frequencies, because the obstruction of the airflow creates considerably more turbulence than for other fricatives. This is rather visible in spectrograms, like this:

See those dark (loud) bands at the top (higher pitch) for /s ʃ z ʒ/? It’s the turbulence.

0·6 days ago

0·6 days agoIf I recally correctly I tried this once, but there was barely any activity. I’m totally OK trying this out again, though, so I’m pinning your post.

0·6 days ago

0·6 days agoJust for clarification, because of the title, they’re talking about the upper basin of the Paraguay river:

As the map shows, and the article mentions later on, that basin is controlled by three governments (the republic of Paraguay, Bolivia, and Brazil).

That said: global warming-wise the situation here in South America is noticeably bad - summers are getting noticeably harsher and there’s something weird going on with the winds, as if they lost power. It reached a point that it affects humans, so of course it’ll affect amphibians, that are far more environment-sensitive.

Deforestation of that basin is also a big concern. It’s happening in territory controlled by each of the three governments - Bolivia, Paraguay and Brazil. It’s mostly about cattle - either grazing lands or soya to feed the cattle. And perhaps not surprisingly not to attend the internal markets, but to export it to lands controlled by governments that won’t need to deal with the environmental impact.

12·6 days ago

12·6 days agoFuck the rules. Buongiorno, capra!

/me does visible gesture in violation of The Law

0·7 days ago

0·7 days agoThe findings raise important questions about how this knowledge is learned, maintained and transmitted across generations, for example, by young chimpanzees observing and using their mothers’ tools, and whether similar mechanical principles determine chimpanzees’ selection of materials for making other foraging tools, such as those used for eating ants or harvesting honey.

Here’s a video showing the process. I’m totally sharing it as informative content, not because it’s cute. (Okay, it’s both.) Check around 1:50 - child is trying to fish termites with a leaf, mum gently picks the leaf from the child’s hand, drops it, and indicates a more appropriate tool.

I think that what’s happening there is:

At the start, a chimp who never fished termites tries random stuff: large leaves, flexible sticks, rigid sticks etc. Some attempts will suck, some will be meh, some good. Based on success cases, the chimp generalises what a good termite fisher should be: long, thin, flexible. Next time they’re going to fish termites, they’ll prefer tools with those attributes, refining further their mental model.

This process is trial and error, so it takes a while. And the time spent is kind of a big deal for a growing child who needs protein. So the mum (or the parents? dunno if male chimps do this) shows good tools, either by example or by direct interference (as in the video).

So it isn’t like the mum is teaching the child the “best” tool; that’s part of the mental model, internalised by the chimp. Instead the mum is guiding the child to develop experiences that they can use to form that mental model.

This has huge implications for human kids. Granted, we have a better communication system than chimps do, but children aren’t exactly experts in that system, so a lot of their learning should resemble how chimps do it. And more than that - perhaps we learn language itself in a similar fashion?

0·14 days ago

0·14 days agoTL;DR: I don’t care about rabbits or hares. I’ll focus on the goddess Ēostre, linguistic reconstruction, and the work of Jacob Grimm. I don’t know if Grimm’s prediction was right or wrong, but I do know that neither his work nor his prediction deserve the disdain this youtuber shows.

Check around 8:00~9:00 for context.

[…] but no direct evidence exists for Ostara, Grimm’s argument was entirely linguistic

[…] then 1000 years later, Jacob Grimm makes a linguistic conjecture, “Ostara”, based on the unsupported assumption that if the English had a goddess Ēostre, the Germanic peoples [SIC] must have had their own version

The youtuber is equating “no direct evidence”, “linguistic argument” = “unsupported assumption”.

Grimm’s prediction is backed up by the comparative method, so neither “unsupported” nor “assumptive”. (Also note the misuse of the word “Germanic”, as if it excluded English speakers - it shows the youtuber doesn’t know what he’s talking about.)

you’re not relying on actual historical evidence, you’re echoing the creative speculations of 19th century German folklorists

Okay, this guy needs to shut up and sod off.

The plural shows he’s assuming Holzmann was a folklorist; he wasn’t. He was a philologist transparently talking about something outside his field of expertise, as it was related to his own field.

Grimm however was a folklorist, plus philologist and linguist. And what Grimm did in Teutonic Mythology was to apply the comparative method to a bunch of words:

- German: Ostern (Easter), Ostermonat (April, archaic)

- Frankish: ôstarmânoth (April; lit. “eastermonth”)

- Old English, Northumbria: Ēastro (the goddess), ēastermōnaþ (April)

- Old English, Mercia: Ēostre (the goddess)

- English: Easter

- Old Norse: austr (east), Austri (a dwarf; more on that later)

- etc.

Proto-Germanic *au becomes Old High German /o:/ ⟨ô, o⟩ and Old English /æ:ɑ/ ⟨ēa⟩ or /e:o/ ⟨ēo⟩ depending on dialect, but it’s kept “as is” in Old Norse. Those words are clearly cognates, so at least the name of the goddess was inherited by Old English from Proto-Germanic, it’s not some random word borrowed from Brittonic or Latin.

Some could say that the word was inherited, but the concept of the goddess wasn’t. So let’s look at the semantic scope of those words:

- April; roughly the start of spring (Northern Hemisphere), when the Sun appears more often.

- a goddess, whose name is clearly associated with #1.

- East; i.e. where the Sun rises

- an immortal dwarf from a set of four (Austri, Vestri, Norðri and Suðri; guess what their names mean), who were tasked by the gods to hold Ymir’s skull (the sky) in place.

All those have to do with the Sun appearing in the sky. With #2 and #4 being clearly religious and related to primordial beings.

Now let’s look into other Indo-European branches:

- (Italic) Latin “aurora”, both “dawn” and its goddess personification. Note that Latin often converts PIE intervocalic *s into /r/.

- (Hellenic) Greek Ἠώς/Ēōs, attested in the Aeolic dialect as Αὔως/Aúōs; note the diphthong. Also “dawn” and a goddess.

- (Indo-Iranian) Vedic Sanskrit उषस्/Uṣás, a goddess. Of dawn.

…isn’t “dawn” when the Sun appears?

There’s an obvious pattern here: Indo-European religions deifying when the Sun appears, often into a goddess. By Ockham’s Razor, the only sane conclusion is that the concept of the goddess Ēostre was inherited by OE speakers from PIE. And if it was inherited, it was present in Proto-Germanic.

So it’s present in the ancestor (Proto-Germanic), one descendant (Old English, North Sea Germanic), and it pops up partially in the religion from speakers of a different branch (Old Norse, North Germanic). Given Grimm’s focus on Germanic languages spoken in the continent, it was only natural to predict that some reference to the goddess would pop up in Old High German (Elbe Germanic). And, if it does, he predicted the name for that goddess through the comparative method - *Ôstara.

All that shit that I said shows that what Grimm did was not unsupported or assumptive. It wasn’t even “creative”. It’s a lot like the predictions Mendeleev was doing with chemical elements following specific patterns based on weight - if you know enough about something in a nascent science, you’re bound to find patterns.

Perhaps Grimm’s prediction was wrong, like Mendeleev claiming that iodine was heavier than measured. Perhaps Elbe Germanic speakers ditched the myth too early to be attested. Or perhaps it’s correct, like Mendeleev’s prediction of gallium, and somewhere in the continent you’ll find a reference to some *Ôstara goddess.

By the way, plenty Germano-Roman inscriptions were found in Germania inferior, containing references to some “Austriahena mothers”. You can find the inscriptions here, look for the text “austriahe”. This (~200CE?) is from Proto-Germanic times, not any specific branch, but it does give some weight to Grimm’s prediction.

0·15 days ago

0·15 days agoSo many nice details:

- the pig bathwater gets piped down as broth

- one of the pigs from the bath gets piped down into the oven

- the pigs running on belts move the cogs pulling the noodles from the machine

0·18 days ago

0·18 days agoIf that’s their goal then it was a really dumb idea to pick these conlangs. It simply won’t show any surprising data, since all of those languages implement recursion in one or another way.

0·18 days ago

0·18 days agoI’m curious if there’s some overlap between conlangs and programming languages, on the region level if not the network level.

I predict that, if there is such overlap, natural languages will also overlap the same way. Because in practice there’s no individual difference between a highly developed conlang and a natlang.

0·18 days ago

0·18 days agoI’m not surprised.

All of those constructed languages were modelled after natural languages, either to give a tongue to some fictitious people (most of the listed) or to perform like an auxiliary language (Esperanto). So the difference between conlang and natlang here is just one of origin.

In the meantime, those programming sets of instructions (Python, C, etc.) were created for something else, issuing instructions in code. On the very best you could analyse them as doing a fraction of what a language does, but in practice it’s something else entirely.

Oh, that gets real fun if you backtrack into Proto-Indo-European cognates using the same root, *h₂ews- “sunrise” - all of the following are cognates:

And it is not even the worst etymological mess I’ve seen. Like Portuguese getting, like, a half dozen words from Latin ⟨macula⟩.